This former West Virginia coal miner-turned-sheriff has had enough of the epidemic. He’s baptized, coached, arrested, sentenced and buried too many neighbors and friends.

McDowell County, W.VA.—Martin West is the blue-eyed, gravelly-voiced, crew-cut man you would cast as a Southern sheriff if this was a movie. He looks like Jackie Gleason as the comical character Buford T. Justice in Smokey and the Bandit, right down to the pencil-thin mustache.

But this is real life.

West is sheriff of McDowell County, the southernmost county in West Virginia, at one time called “Little New York” by locals. Others called it “The Free State of McDowell” because of its politics and diverse population. But nothing feels like freedom here anymore.

Once a bustling home to nearly 100,000 residents, McDowell County was nationally known as a leader in coal production. At the time it was the third most populated of the state’s 55 counties and was an important part of the state’s economy. But as the industry tapered off, beginning in the 1950s, younger residents moved away leaving mostly seniors and others who couldn’t afford to move.

Today, for every well-maintained traditional Southern home, there appear to be two or three deserted or dilapidated structures. Less than a third of people over 16 years old are part of the civilian workforce. One survey found that almost half of all personal income in the county is from federal assistance programs.

It is now the poorest county in the state, with the lowest level of employment and a high rate of health problems. It is near the top in obesity—and suicide rates.

It also has the lowest life-expectancy rate of any county in the U.S.—and the highest rate of drug-induced deaths nationwide, a rate nearly 10 times the national average. The most recent census shows the county’s population has been decimated—and more are dying there every day.

The loss of coal jobs severely hurt McDowell County. The pain pill addiction epidemic may well kill it.

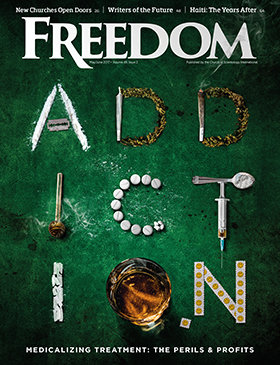

Early in the opioid crisis, over a six-year period, pharmacies in McDowell County were shipped 12.2 million hydrocodone and oxycodone pills, for a population of less than 30,000. No one questioned it—pharmacies kept selling them, often without asking for or verifying a prescription. Distributors chose not to report the massive demand increase to the DEA—as they’re required to do—and instead just kept delivering more and more pills. Manufacturers were glad to keep distributors busy.

As a result, millions of pills were sold and resold all around the region—for pain, and recreational use as well.

Today, as many as 20 percent of this county’s residents are estimated to be addicted to prescription pills, heroin or synthetic opioids. The county has the highest number of overdoses per capita in West Virginia—the state leading the nation in deaths per capita. Pending lawsuits against drug manufacturers are tied up for months and years. There is distant hope that suing the distributors will bring a cash settlement large enough to at least provide for rehabilitation and education.

Sheriff Martin West has seen it all. Now 63, he grew up in McDowell County. A former coal worker, he later served as a county commissioner, as pastor of a small church and as a local magistrate for 27 years. West won re-election as sheriff in 2016 and is now in his sixth year in office.

Crimes associated with a drug crisis call for more law enforcement, but budget cuts have forced West to reduce the number of deputies from 14 to 10. West said the state seems to have forgotten his county, refusing to send financial help for rehab, law enforcement and more to cope with the opioid epidemic.

The weight of the county’s despair is evident as he sits in the “new” sheriff’s department, a leased brick structure at the end of the town’s main street. The sheriff, who painted the interior walls himself, prefers the current structure because the roof doesn’t leak like the old building.

Answering questions

Sheriff West talked with Freedom about the challenges he faces, the county’s decision to sue drug wholesalers for causing “addiction and destruction” motivated by profit—and the hope of McDowell County residents.

Freedom: Can you tell me your take on how addicts in the county got started?

Sheriff West: Some of them were in bad situations; they’d had surgeries for knees, different replacements, and got addicted to the pain pills. A lot of them have money, better living conditions and jobs, but still got addicted. Some of them just turned to drugs, but for a lot of them it was pain pills.

How would you describe the drug problem here today?

Heroin’s coming back strong, because it’s cheaper to make. There are drugs on every corner. And what used to be only the lower class, poor people—now it has affected every different social status: rich people, middle income, low income.

Do you find people you wouldn’t expect to be in this situation, suddenly involved in or overdosing on drugs?

Nothing surprises me anymore. When I was a magistrate, they’d bring people in that you’d never think would be involved with drugs. Sometimes it’s whole families. I’m a pastor at a local church, and I’ve buried several members from the same family.

I’ve dealt with family, friends, neighbors, business people, school employees. These are people that I knew personally. It got me upset. These are people to me, they’re not numbers.

What led to the county’s lawsuit against the distributors (Cardinal Health, McKesson Corp., AmerisourceBergen and a local physician)?

We were the first county in West Virginia to sue distributors. I contacted the attorney general to get some relief. We need it for all the prescription pills that were being dumped into this county, the people that were dying of overdoses. It’s in federal court now.

My hope is that we could get some help for this county, some facilities in here, and more people out in the community to help. There’s not a single bed in this county for detox, or rehab, but we lead in overdose deaths per capita.

What sort of hope do the people feel?

The main resource of this county, and that West Virginia has, is the people. We are a resilient people. A lot of people could have left, they had the resources, but this is home. They love the people here and they love where they live.

I’ve been that way myself. I could have gotten up and left. I had opportunities many times. My wife’s the vice-president of the Board of Education. We’ve always been community-oriented. We stay involved to help people. We care about what we do.

We need some help here. In 2016, the overall death rate here (for overdoses) was 47 per 100,000. I’ve been to ground zero in New York. This is ground zero in West Virginia.