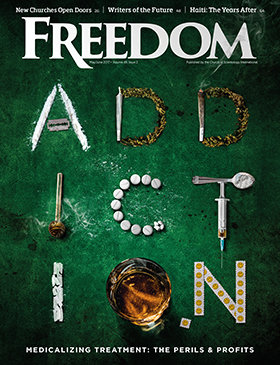

In West Virginia’s natural paradise pain pills paved a road to perdition.

Charleston, W.VA.—Just outside the airport here is a sign welcoming visitors to West Virginia. “Wild and Wonderful” it boasts, and the “wonderful” is immediately on display with a transcendent beauty that inspires songs.

Country roads, Blue Ridge Mountains, the Shenandoah River and stunningly green ancient forests of Norway and Sycamore maples, Horse-chestnuts and Ailanthus altissimas, also called the Tree of Heaven.

“Almost heaven,” the song says. Almost. But not quite. Three minutes from the airport is the first of many billboards advertising drug rehabilitation.

Welcome to ground zero.

In a nation overcome with an opioid epidemic, West Virginia—ranked 38th in population and 48th in income—is No. 1 in overdose fatalities per capita. In 2016 the rate was 52 deaths per 100,000—the second consecutive year with an increase of more than 16 percent. They had 33 percent more overdose fatalities than neighboring state Ohio, which ranks second at 39.1 per 100,000.

West Virginia is also No. 1 in what the opioid epidemic is costing the state—$8.8 billion a year, or 12 percent of the state’s gross domestic product (GDP), according to a study this year by the American Enterprise Institute. That study considers what each state spends on health care, substance abuse treatment, criminal justice costs, and projects lost worker productivity to estimate the overall societal burden of fatal overdoses.

By that measure, West Virginia is well ahead of the rest of the country—the only state with a double-digit percentage of its economy lost to the opioid epidemic. In a state with an annual budget of less than $5 billion, the study places the annual cost here at nearly $4,800 per resident, some 40 percent more than the nearly $3,400 per resident the epidemic costs second-ranked Maryland—about 5.4 percent of its GDP. Eight other states come in at between 4 and 5.3 percent; the rest are below that. “We’re losing $8.8 billion per year, at least one-eighth of the economy,” said Dr. Rahul Gupta, West Virginia’s public health commissioner.

Located in the heart of the economically ravaged Appalachian coal belt, it is said that this is where the opioid epidemic began. Workers in coal mines—and eventually, anybody with a toothache, sore elbow or sprained knee—were eager for 12-hour, supposedly nonaddictive pain relief. Because doctors were encouraged—and sometimes rewarded—by manufacturers to treat every single pain complaint with pain pills, the path to addiction was paved on these country roads.

Before long, patients of all walks of life who had taken pain pills on the advice of their doctors—pills strong enough to soothe stage-four cancer patients—found themselves addicted to opioids. Soon, many of the addicts were crushing pills to snort, smoke or inject the drug as they fought off the withdrawal sickness when opioid levels subsided.

No alarms sounded as prescriptions and refills spiraled beyond plausible numbers; distributors loaded up pharmacies with more pills. Between 2007-2012, distributors sent more than 780 million hydrocodone and oxycodone pills into the state, 433 pills for every man, woman and child. During that time, a Charleston Gazette-Mail investigation found, 1,728 West Virginians died from fatal overdoses of those two drugs.

But the flood of pills continued. One town of 400 residents was sent 9 million opioid pills in two years. Another, with less than 1,800 citizens, received 16.5 million in 10 years. Another, population 2,900, received almost 21 million pills during that decade.

Addicts from other towns and states drove in to stock up—both for use and for resale. That pattern was repeated in varying degrees across the country. When new laws mandated tamper-proof pills and prescription regulations, illegal drug dealers stepped up and offered a cheaper and more accessible opioid: heroin, often “cut” with even more dangerous and more powerful synthetic opioids. Today, the entire nation has been affected by this epidemic—some states worse than others. But West Virginia is still No. 1, and nothing indicates that this will change anytime soon.

It’s estimated that 20 percent of residents here are addicted to opioids of some kind. In 2016, when awareness of the crisis was already public knowledge, the state saw a 21 percent increase in opioid overdose deaths from the previous year, and a 25 percent increase in all drug overdose deaths.

One resident in Huntington, West Virginia has taken to driving a hearse around the state painted with the phrase: “Heroin Hearse: Is This Your Last Ride?”

Huntington, with a population of 48,000, saw 26 overdoses in less than four hours on a single day last year, the result of a shipment of either a strong batch of heroin, or a batch laced with synthetics like fentanyl. Remarkably, none of those patients died—thanks mostly to well-practiced first responders who were able to quickly administer naloxone, a drug that can prevent death from an opioid overdose.

Seemingly a miraculous lifesaver, a recent study shows that naloxone is now standard equipment for police and firefighters, as well as teachers, librarians and even addicts. And that, the study says, leads to more opioid abuse—because addicts live to shoot up another day.

That is where the opioid crisis is today—even the good news is bad news.

Freedom magazine spent five days in West Virginia, in several cities, talking to officials in law enforcement, government and health care—and also talking to civilians, people on the street, in restaurants, at work—and to addicts. They share a common story and all are somehow directly affected by this epidemic—either as a recovering or current addict, as a caregiver for an addict or an addict’s children, or as a member of a family of an addict.

From the hotel van driver who lost three friends to overdoses, to the administrator at the needle exchange program who sees people pick up clean needles and never return; from the waitress who left her job in the foster care system because she’d gotten tired of rescuing children from homes where their parents had overdosed, to the mayor of Charleston, whose son has multiple arrests because of opioids—it seems everyone in this state has been touched by this.

“My son’s hooked on heroin,” Mayor Danny Jones told Freedom during an interview on his weekly radio show. “It’s broken up families, it’s killed friends. I don’t know how my son stayed alive, and he’s in jail as we speak.

“You don’t have to be some red-hot liberal to understand the damage that has been done by the pharmaceutical companies to our region,” said Jones, a former sheriff. “It’s getting worse. It’s still getting worse.”

Since that interview, the mayor’s son Zachary, who had already been to at least three rehab facilities, was bailed out of jail by friends while awaiting trial. According to police, he then went on a “drug-fueled crime spree,” committing multiple burglaries. He pleaded guilty to charges earlier this year.

For perspectives on how bad things are in West Virginia, Freedom spent time with two men who’ve seen the human toll up close: a lawyer and a sheriff. They were both born and raised here—and are appalled by what they’ve seen.