And when you don’t have the staff to handle your patient load, you shouldn’t increase it.

But at the Bay Area’s Santa Rosa Behavioral Healthcare Hospital, neglect and stupidity—coupled with a state agency’s toothless and apathetic oversight—have brewed up nearly a decade’s worth of disasters since the facility first opened in 2016.

“The system is broken,” said Charlene Harrington, a former top regulator.

An eye-opening investigation by the San Francisco Chronicle—a review of damning reports, unfulfilled “plans of correction” and dozens of interviews with experts, regulators and current and former employees—paints a nightmarish hellscape at the for-profit facility run by Signature Healthcare Services, one of the largest privately held behavioral hospital companies in America.

And all without so much as a wrist slap from the California Department of Public Health (CDPH), whose responsibility it is to license hospitals, respond to patient and worker complaints and provide oversight and accountability.

A sampling:

- Management “solved” the understaffing crisis by assigning a clerk from the business office to watch patients (like asking your gardener to remove your appendix).

- A 12-year-old girl said a male nurse made her touch his genitals. The accused nurse was allowed to write his own internal incident report. Why? “Adolescent patients made accusations of sexual abuse all the time,” a hospital employee said. About two months later, a second female patient made a nearly identical claim, at which point the matter was finally reported to authorities. Hospital administrators ultimately concluded that both attacks “appeared to have happened” and it was “not a good idea to have the perpetrator complete an incident report against himself.”

- Patients with suicidal urges in need of constant supervision went neglected or unsupervised, resulting in suicides.

- One teenage patient in particular attempted suicide and a doctor ordered an employee to be within arm’s reach of her at all times. Staff ignored the order, and the patient was subsequently sexually assaulted by another patient who was supposed to be monitored full time. Staff then filed false reports to protect themselves, insisting they were watching the patients the whole time.

Notified of these atrocities, the CDPH did what it’s always done in response to the dozens of human rights violations reported at Santa Rosa Behavioral: request a “plan of correction.” Santa Rosa then submits its plan of correction—usually a promise to get more staff or supply hall monitors—and then forgets its promise until the next catastrophe.

The CDPH does have the power to do more. It has broad discretion. It can hold care facilities-turned-Bedlams accountable. It can issue fines of up to $125,000 for violations of state or federal regulations. It can refuse to issue licenses. It can forbid hospitals from accepting patients until their concerns are addressed. But the CDPH has a soft spot in its regulatory heart for for-profit psychiatric facilities.

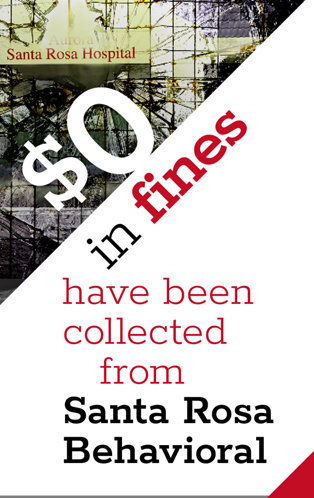

Out of hundreds of safety violations it has logged for 21 such California for-profit facilities since 2019, it has collected a pittance: $94,200. That’s less than the maximum allowed for a single fine. And exactly zero dollars have been collected from Santa Rosa.

“The system is broken,” said Charlene Harrington, a former top regulator at CDPH and professor emeritus of social behavioral sciences at University of California San Francisco, who reviewed the Chronicle’s findings. “If they are not giving fines and penalties or placing holds on admissions, they aren’t going to be successful because there are no teeth.”

While answering no specific questions about its kid-glove approach to for-profit psychiatric hospitals, the CDPH did issue a statement protesting its good intentions in a boilerplate: “Ensuring hospitals at all levels are adequately staffed, and that proper care is provided to patients, is a crucial part of our mission to protect the quality and safety of health care for all Californians.”

“I am surprised that their doors are still open.”

Santa Rosa’s mother ship, Signature Healthcare Services, did likewise, saying: “Each hospital takes all incidents and negative outcomes seriously, investigating and adjusting protocols or retraining staff to prevent recurrence.”

At least five times, administrators have promised to institute systems to promptly inform health officials, child protective services or law enforcement about instances of abuse.

That hasn’t happened.

At least eight times, they’ve promised to better staff units or monitor at-risk patients.

That hasn’t happened.

Each time health inspectors check, they find that even minimum standards aren’t met, cite them and get a promise to do better. Then the script repeats again, like a washing machine stuck on a rinse-spin cycle.

Employees told CDPH last March that patients received no treatment while being warehoused in their rooms like “caged animals.”

“There is so much pressure to get more patients, ‘heads in beds,’” the hospital’s director of nursing told state health inspectors last spring, adding that patients were admitted “without considering if we had enough staff to safely care for them.”

After speaking to the inspectors, the nursing director resigned.

“I am surprised that their doors are still open,” said Lily Akers, a former Santa Rosa Behavioral nurse.

With so many “negative patient events”—as these atrocities are called in psych-speak lingo—it is, indeed, quite the surprise that Santa Rosa and its 20 sister for-profit dealers-in-abuse are still in business.

One could almost dare to suspect an unholy quid pro quo in the works between the psychiatric facilities and their CDPH watchdogs—at the cost of human lives.

At any rate, we can thank our stars that the CDPH wasn’t put in charge of Holocaust architect Adolf Eichmann.

They likely would have let him go on his word that he wouldn’t do it again.