Education Minister Bernard Drainville is pushing to enact Bill 94, which expands the restrictive, anti-religious demands of 2019’s Bill 21. Bill 21 bans teachers, prison guards, police officers, judges and other public employees in positions of authority from wearing symbols of their religion—including yarmulkes, hijabs, turbans and crosses—while at work. Canada’s Supreme Court intends to hear cases in opposition to Bill 21.

Bill 94 would expand the restrictions from public school teachers and principals to all school workers and volunteers, including parent volunteers, lunch and after-school monitors and secretaries and librarians. Even parents picking up their children from school could not wear face veils if they so choose, and the bill bans full-face coverings among girls in schools.

“It’s a question of principle. In Quebec, we cannot accept that students have their faces covered in a classroom,” said Drainville, citing the necessity of protecting the “values of Quebec.” “We made the decision that state and religion are separate. And today we say the public schools are separate from religion.”

“The message that is sent is, don’t participate in my society, stay home, don’t pay my taxes, don’t be a good citizen, just isolate yourself.”

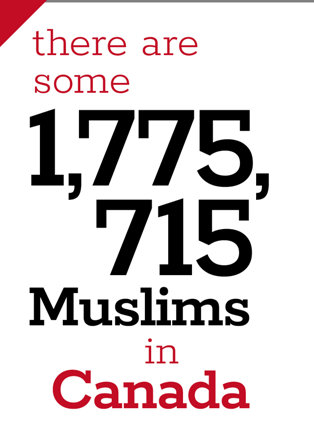

Muslims, wearing hijabs and praying multiple times per day, are perhaps the most visible group to be affected by this legislation, and there can be little doubt that a shift in Quebec’s population is playing a role in support for the restrictions, largely aimed at Muslims. Specifically, between 2001 and 2021, the population of Muslims in Quebec leapt from 108,620 to 421,710 and the number of Muslims in Canada overall shot up from 579,640 to 1,775,715 in that same time period—all of which suggests Quebec, if successful, likely won’t stand alone for long in endeavoring to legislate restrictions on faith.

But Muslims are fighting back.

Shaheen Ashraf is a board member of the Canadian Council of Muslim Women. She wears a headscarf, and said: “The message that is sent is, don’t participate in my society, stay home, don’t pay my taxes, don’t be a good citizen, just isolate yourself.”

Joe Ortona, the chair of the English Montreal School Board, favored the Supreme Court’s decision to review Bill 21, the original legislation placing restrictions on religion.

“The law runs contrary to our values as a society,” he said. “It’s contrary to the Quebec and Canadian charters. And our hope is that the courts will recognize that and ultimately strike down the law.”

In a joint statement, the province’s justice minister and secularism minister, on the other hand, stated: “It is primordial, even vital, for Quebec to be able to make its own choices, choices that correspond to our history, to our distinct social values and the aspirations of our nation.”

Quebec Premier François Legault even wants to ban praying in public.

“Seeing people praying in the streets, in public parks, is not something we want in Quebec,” he said. “When we want to pray, we go to a church, we go to a mosque, but not in public places. And yes, we will look at the means where we can act legally or otherwise.”

He added: “Today I want to send a very clear message to the Islamists. We will fight, and we will never, never accept that people try to not respect the values that are fundamental to Quebec.”

“No one should impose on a woman what she needs to wear or not wear.”

The spark that set off the recent fire came at Bedford Elementary School in Montreal. Teachers there were accused of promoting Muslim values, setting off a 90-page government report of condemnation, as well as the suspension of 11 teachers and the removal of their teaching licenses. Most of the teachers were Muslims from Northwest Africa.

Quebec also launched investigations of 17 schools suspected of violating the province’s secularism law.

The United Nations and the United States have taken positions diametrically opposed to those of Quebec.

“No one should impose on a woman what she needs to wear or not wear,” Marta Hurtado of the UN Human Rights Office said. “According to international human right[s] standards, restrictions of expressions of religions or beliefs such as attire choices are only acceptable under really specific circumstances that address legitimate concerns for public safety, public order or public health or morals.”

In 2023, Pennsylvania became the last state in the US to drop bans against teachers wearing religious symbols in schools.

The most important goal, of course, should not be upholding secularity at any cost, but preserving and defending the fundamental human right of religious freedom.

We get that. The UN gets that. Most of the rest of the world gets that.

Why doesn’t Quebec?

The only solution is tolerance—the ability to co-exist with folks who are different from you.

When government types start talking about controlling how people worship, how they pray and what religious clothing they choose to wear, it’s a very dangerous path to walk down—because when you start cheering on the authorities to go after one set of religious believers, it may not be long before they come after you.

We’ve seen it before, of course, when Nazi Germany went after the Jews and the Gypsies, and then homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, political opponents and anyone else they didn’t like.

We all know how that ended.

As L. Ron Hubbard wrote in the common sense guide to better living The Way to Happiness: “Religious tolerance does not mean one cannot express his own beliefs. It does mean that seeking to undermine or attack the religious faith and beliefs of another has always been a short road to trouble.”

A short road to very big trouble. For every one of us.

So here’s a better idea than forcing people to stop advertising their religious beliefs: Let everyone live and let live.

Let us try getting along together.

In other words, let’s try peace.