The international study, published March 18 in the medical journal Addiction, serves as yet another stark reminder of an escalating crisis—and the urgent need to curb its deadly spread.

Led by researchers from the University of Queensland, the study examined 683 wastewater samples from 68 locations, including the US, Australia, Brazil, China, Nigeria and the UK.

Just how—and why—the compounds are ending up in wastewater is far from clear.

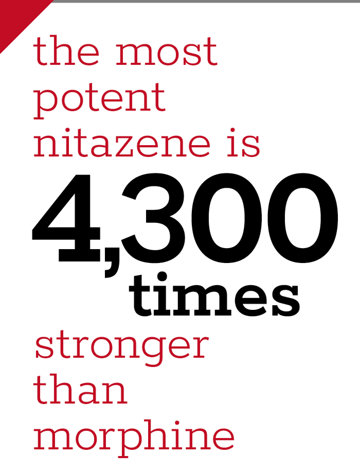

The analysis detected two chemically manufactured drugs—protonitazene and etonitazepyne—that belong to a class of extremely potent synthetic opioids known as nitazenes. Although both protonitazene and etonitazepyne are nationally and internationally controlled, they are associated with deaths among users, not least because the drugs’ consumption is recreational and illegal rather than medically supervised.

Water treatment plants aren’t equipped to remove every trace of drugs and pharmaceuticals, which means, in theory, nitazenes could end up in drinking water, too.

Protonitazene is a Schedule I controlled substance in the US. The US Drug Enforcement Administration considers it “an imminent hazard to the public safety” because the drug is estimated to be about three times more potent than fentanyl, a notorious synthetic opioid already associated with hundreds of thousands of overdose fatalities and considered the leading cause of death among drug users in the country.

Notably, in Australia, protonitazene has been identified in yellow powder mis-sold as ketamine, an anesthetic that has hallucinogenic properties, the abuse of which has led to severe hospitalizations. Further, users expecting ketamine may not recognize the signs of an opioid overdose and can be blindsided when dangerous reactions occur, thereby increasing the risk of fatal outcomes. Protonitazene has also been found as an adulterant in substances sold as cocaine, further elevating the risk of unintentional overdose.

Etonitazepyne, another nitazene, which goes by the street name pyro, is up to 40 times more powerful than fentanyl, and that high potency significantly increases the risk of respiratory depression, overdose and death—even with minimal exposure.

Australian researchers detected etonitazepyne in wastewater samples in early 2024, marking the first time the synthetic opioid was identified in the country’s wastewater.

Just how—and why—the compounds are ending up in wastewater is far from clear. Originally developed in the 1950s by Swiss researchers as opioid analgesic alternatives to morphine, nitazenes were never approved for medical use and remained largely absent from the illicit drug market for decades. Prior to 2019, they were mostly known only within scientific circles, with few notable instances of recreational use—most prominently, incidents in Moscow involving the deaths of 10 users in 1998.

“Synthetic opioids can be so potent, there is serious concern for frontline workers like emergency hospital staff.”

Since their broader appearance on Europe’s illicit drug scene six years ago, nitazenes have been detected across nearly every continent. Yet despite their growing global presence, the compounds remain under-researched and rarely discussed, even by major health agencies. As of June 9, 2022, a search for “nitazene” on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website returned no results—though the substances were occasionally mentioned in passing within articles focused on fentanyl.

Whether the discovery of protonitazene and etonitazepyne in Australian wastewater resulted from the drugs’ direct disposal into wastewater rather than through human consumption is unknown, but the finding underscores the drugs’ potential infiltration into new markets and highlights significant public health concerns.

Between January 2023 and September 2024, the Australian Border Force (ABF) intercepted 64 shipments of nitazenes. The drugs primarily arrived through the international mail system and originated from Hong Kong, Britain and Canada.

“Synthetic opioids can be so potent, there is serious concern for frontline workers like emergency hospital staff, ABF officers and [Australian Federal Police] forensics members, who could be exposed to fatal health effects through inhalation and exposure when handling the substance,” AFP Commander Paula Hudson said in a December 2024 news statement.

In the US, etonitazepyne has been linked to overdoses, according to the Department of Justice, and the drug’s presence has exacerbated the nation’s opioid epidemic. Since it began in the late 1990s, the opioid crisis has defied federal and state level efforts to solve it, claiming nearly 727,000 lives from overdoses related to prescription and illegal opioids between 1999 and 2022, according to the CDC.

Without decisive action, synthetic opioids will continue to fuel an unprecedented wave of deaths. It is imperative for governments and communities to act swiftly and comprehensively against a danger as clear and present as this.