Published March 19 in JAMA Psychiatry and led by researchers from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the study draws on data from more than 83,000 adults aged 18 to 64, using prescription tracking databases and the 2021–2022 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health.

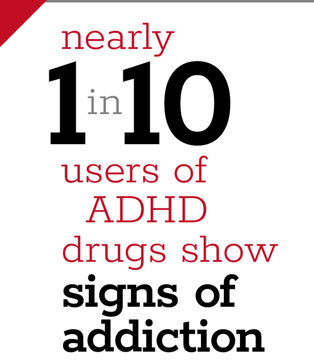

The findings are startling: Among those prescribed powerful, addictive stimulants at the heart of the crisis—like Adderall (a mixture of four amphetamines), Ritalin (methylphenidate) or Desoxyn (methamphetamine)—25 percent report misusing them, and nearly 1 in 10 meet criteria for what the study calls “Prescription Stimulant Use Disorder” (PSUD).

According to the study, 72.9 percent of those addicted to these drugs had only used their own prescriptions.

Ritalin, one of the most widely prescribed ADHD drugs—for which no safety and efficacy studies exist for children under six, breastfeeding mothers or the elderly, according to the Mayo Clinic—is classified by the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule II controlled substance, placing it alongside drugs like morphine, opium and cocaine because of its high potential for abuse. According to the DEA, stimulant ADHD drugs can cause “severe psychological or physical dependence” and are considered dangerous, a fact that casts a troubling light on the growing number of individuals now labeled with PSUD.

According to the study, 72.9 percent of those addicted to these drugs had only used their own prescriptions, undermining the narrative that misuse is simply about diversion or irresponsibility. What’s more, nearly half of those the study deemed as having “PSUD” reported no misuse in the conventional sense, suggesting that even routine, “by-the-book” use of these drugs can lead to dependence.

The most commonly prescribed stimulants—amphetamines—pose the greatest risk, with misuse rates three times higher than methylphenidate and addiction rates more than double. Nevertheless, these drugs continue to be marketed as “safe and effective.”

At the core of the crisis is the label “ADHD” itself. Instead of acknowledging that attention span and activity levels naturally vary from person to person, shaped by individual personality and environmental factors, “ADHD” groups millions of adults with “symptoms” that are common and subjective.

But forget that ADHD drugs are frequently prescribed for normal behavior—the deeper scandal lies in the fact that these drugs alter brain chemistry, and that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, not only are children as young as three being labeled with ADHD and drugged, but there are as many as 5.7 million physician office visits in which “ADHD” is the ultimate “diagnosis.”

The American Psychiatric Association’s role in promoting this “diagnosis,” especially given the organization’s close ties to the pharmaceutical industry, is well known. A 2012 study published in PLOS Medicine found that 69 percent of DSM-5 task force members had financial relationships with drug companies, a shocking conflict of interest.

Clearly, the drugs are driven less by science and more by profit.

The highest surge in ADHD “diagnoses” is occurring among middle-aged women. From 2019 to 2022, prescriptions among women aged 35 to 64 jumped from 1.2 to 1.7 million, the National Institute on Drug Abuse study reports, indicating a calculated expansion of the market, enabled by telehealth, lax oversight and the growing medicalization of everyday life struggles.

Even mainstream sources like the DEA have taken note. In 2022, the agency warned stimulant manufacturers about aggressive marketing tactics—comparing the current trajectory to the opioid epidemic that has already claimed hundreds of thousands of lives.

The study’s authors recommend increased screening for addiction among those prescribed psychotropic stimulants, even those following their prescriptions to the letter. But this misses the larger issue: Why are millions being drugged in the first place?

When normal human behaviors like restlessness, inattention or emotional variability are medicalized and “treated” with mind-altering chemicals, the line between care and control becomes dangerously blurred. The more psychiatric drug use under the guise of “treatment” is normalized, the more society risks obscuring the true forces that contribute to human distress in the first place.