“Freedom of religion is guaranteed to all.”

—Article 20, The Constitution of Japan

Japan learned its lesson so well, in fact, that after the war, it agreed to a new system of government under an American-drafted “Peace Constitution,” guaranteeing freedom of speech and religion.

That constitution is, today, the world’s oldest unamended constitution, and Japan’s adherence to it has made the island nation one of the world’s most stable democracies.

So when a Tokyo court ordered the dissolution of the Unification Church (UC), the world was stunned.

Attacks on the religion exploded. Forgotten was the murderer.

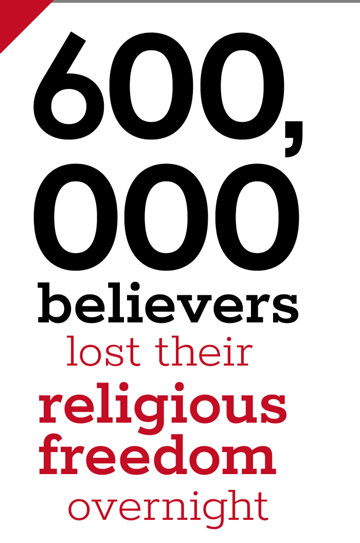

The repercussions for the faith, now officially known as the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, include revocation of its legal status—which removes its tax-exempt privilege and requires its assets to be liquidated—and the stripping of its 600,000 parishioners of their rights as a religious community.

The court’s action is a warning shot across the bow of other faiths currently thriving in democracies. Be they large or small, they must take heed, as shown by the fate of the UC, that the religious freedom they currently enjoy can disappear in an instant.

But it wasn’t the church’s beliefs that were seen as dangerous, it was their politics. Staunchly and aggressively anti-Communist since its founding in the early 1950s, the UC has, for decades, been a strong voice championing human rights, representing a threat to Japan’s Communist Party.

The party and its allies, in reply, mounted a savage campaign of hate against the church.

Then on July 8, 2022, former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was assassinated. The murderer, Tetsuya Yamagami, disgruntled about his mother’s membership in the UC, said he targeted Abe because Abe supported the church.

Attacks on the religion exploded. Forgotten was the murderer. Demands to investigate the church drowned out all other concerns—even that of bringing the perpetrator himself to justice.

And the media took it and ran. Rev. Tomihiro Tanaka, who heads the Japanese branch of the church, called out the rampant bias that “encourages religious discrimination against the UC.”

“Our churches in Japan,” Rev. Tanaka said, “have been subject to death threats and threatening phone calls, abusive language blasting out of sound trucks and obstruction of assemblies.”

Assassin Yamagami, on the other hand, after nearly three years, has yet to be tried. In those same three years, the UC has been tried, found guilty and sentenced to oblivion for no crime.

In dissolving the UC, the Japanese government committed, according to author and European Federation for Freedom of Belief Advisory Council member Marco Respinti, “probably the most serious and reckless act of interference by a democratic government against a religious community since World War II.” Consequently, the nation has been shouted down from across the ocean by one of Japan’s strongest allies, the United States.

Former US Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom Sam Brownback and former House Speaker Newt Gingrich have spoken out against the Japanese government’s violations of freedom of religion and fundamental human rights.

Coincidentally, the news of the Tokyo court’s ruling broke while, 7,000 miles away, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) released its annual report in Washington, DC.

As America’s designated watchdog for religious freedom throughout the world, USCIRF is charged with singling out those countries of particular concern (CPCs) for egregious violations of freedom of religion, as well as assembling a special watch list (SWL) of nations engaged in or tolerating severe violations of the right to worship.

USCIRF has never before included one of the world’s major advanced democracies on either list.

But there is a first time for everything.