The imbibers of our new pharma-laced waterways are those who inhabit them: marine life.

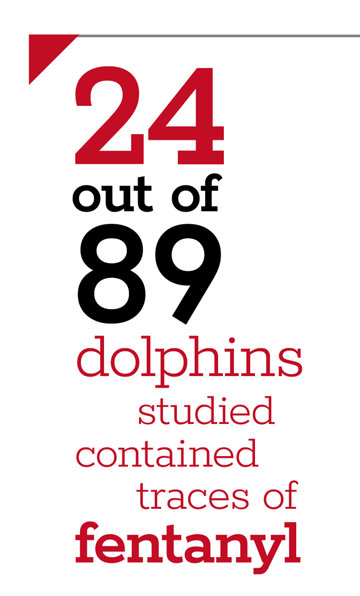

In the Gulf of Mexico, it was the dolphins—24 out of 89 dolphins studied contained traces of fentanyl. Texas A&M University-Corpus-Christi Chemistry Professor Hussain Abdulla called the findings a “red flag” that pharmaceuticals are making their way on the global ecological stage as a growing micropollutant threat. “There is a concern here and we need to look,” he said.

The addicted fish chose meth water; non-addicted fish had no such preference.

Dolphins that ingested fentanyl and occupy waters near the Mexican border, where drug smuggling via the Gulf has become popular, could be a clue to where the synthetic opioid is coming from.

An earlier study showing sharks in Brazil with cocaine in their system indicates that fentanyl isn’t the only drug to worry about.

“We need to investigate it further and [see] how big that problem is,” Professor Abdulla added. “Is it only local in the Gulf of Mexico or is it actually worldwide?”

It’s already been investigated, Professor, and, yes, it is worldwide.

UK scientists in 2019 reported cocaine in freshwater shrimp in 15 out of the 15 rivers they sampled.

Two years later, a paper published in the Journal of Experimental Biology read: “Our results suggest that emission of illicit drugs into freshwater ecosystems causes addiction in fish and modifies habitat preferences with unexpected adverse consequences.”

Specifically, meth addiction in wild fish is causing changes in their behavior with catastrophic results. Researchers put “meth-addicted” brown trout into “withdrawal” (i.e., in drug-free tanks) for 10 days, during which time they were tested as to their preference: freshwater or meth-contaminated water. The addicted fish chose meth water; non-addicted fish had no such preference. The addicted fish also had indicators of drug withdrawal. They moved less—a sign of stress—with “interest” in activities like eating or reproducing potentially waning as a result. The researchers further speculated that such a change in natural behavior could affect their ability to survive, being less likely, for example, to evade predators.

“Active pharmaceutical ingredients are found in waterways all around the globe, including in organisms that we might eat,” Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Assistant Professor Michael Bertram, the study’s co-author, told The Guardian in June. “There are a few pathways for these chemicals to enter the environment. If there is inadequate treatment of pharmaceuticals that are being released during drug production, that’s one way. Another is during use. When a human takes a pill, not all of that drug is broken down inside our bodies and so through our excrement, the effluent is released directly into the environment.”

An examination of the brain chemistry of drug-exposed fish revealed changes that parallel those in human addicts; the brain markers lingered even after the behavioral changes had faded—indicating that, just like humans, drug exposure can have long-term effects on other species as well.

All told, chalk it up as an evolutionary step backward, and fully man-made.

We thought our societal problems were taking us to hell, but we were wrong.

They’ve gone underwater instead—home to 94 percent of all life on Earth.