The result, according to the EU Drugs Agency, is a more than $12 billion cocaine market in Europe alone.

“With these profits, these organizations manage to permeate all public and private institutions, corrupting any structure,” said Willian Villarroel, Ecuador’s former anti-narcotics director.

“A few years ago, people were saying the future is synthetic drugs.… Right now, it’s still cocaine.”

How did this happen? Where did it begin?

Well, how do many profitable enterprises begin?

They start with making friends.

That’s what Dritan Rexhepi did. But not just any friends.

After escaping jails in his native Albania—then Italy, then Belgium—on charges of murder, drug trafficking and robbery, Rexhepi fled to Ecuador around 2011. There, he built a drug trafficking network based on relationships with legitimate businesses willing to front him in exchange for a share of the huge profits that come with the industrialization of drug abuse.

Arrested and jailed again in Ecuador in 2014, Rexhepi continued to build his empire, befriending key Latin American gangs while converting his prison cell block into executive offices. (The Ecuadorian prison system had long since passed out of the hands of law enforcement and into the hands of the gangs. To wit: When an inmate enters Litoral Penitentiary in Guayaquil, Ecuador, it’s not the guards who decide what cell block to place him in and with what offenders—it’s the gangs.)

Rather than pit his own cartel against others in competition like so many before him, Rexhepi fostered cooperation in the interest of universal profit—bringing us to the situation as it stands in 2025: “It’s not about how many people you have,” Fatjona Mejdini, a Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime analyst, explained recently. “It’s about the right alliances you can form.”

Those alliances and others have spread cocaine throughout nearly all of Latin America’s mainland nations and into Europe, which now rivals the US as the world’s top destination for cocaine, with the demand for the drug exploding on the continent.

By working with fellow drug trafficking cartels, not against them, the Rexhepi-led Albanian kingpins have transformed and turbocharged the drug trade.

The seizure of 22 tons of cocaine hidden on an Ecuadorian pig farm last year revealed the Albanian trafficking model of teamwork among criminals: Colombian armed groups handle the production and transport across the border and Ecuadorian gangs take it from there. First, Los Lobos transports the drugs to the underground cellar. Then Los Choneros, another gang, guards the drugs, while a third, Los Lagartos, smuggles them into the port. Finally, Los Chone Killers, a fourth gang, deposits and hides the cocaine on a designated container ship.

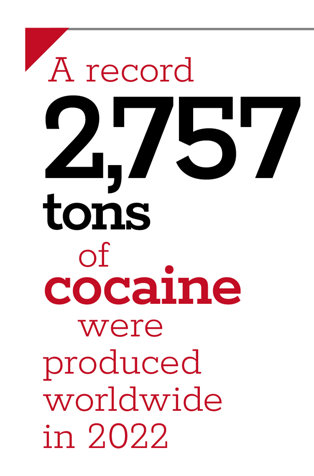

Rexhepi’s story is a microcosm of what is now a global explosion in the cocaine industry—bigger, broader-based and more profitable than ever. A record 2,757 tons of cocaine were produced worldwide in 2022, a 20 percent increase over the prior year, according to the most recent global drug report from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Colombia, the nation producing most of that cocaine, is the fulcrum of the boom. Since the 1993 death of drug lord Pablo Escobar, Colombia has tripled its cocaine crop and more than quintupled the area of land used to farm the drug.

“It’s going up and up and up,” said Thomas Pietschmann, a research officer at the UNODC. “A few years ago, people were saying the future is synthetic drugs.… Right now, it’s still cocaine.”

And what of Rexhepi? In 2021, Italy sought his extradition, warning Ecuadorian authorities (as if they didn’t already know) that the man running a business from behind bars at their federal prison was the “undisputed leader” of an Albanian drug trafficking network with global reach and access to “infinite quantities of cocaine.” A letter from the Italian embassy warned that Rexhepi, “thanks to a dense network of complicity and corruption, from prison, using all types of communication systems,” ordered the murder of rivals and masterminded transatlantic shipments of drugs.

“Wherever there is demand, they are going to be the delivery guys.”

With the prospect of being handed over to law enforcement in Rome, Rexhepi knew it was time to get out of Dodge. “Conveniently,” a local judge—later dismissed for decisions that benefited drug lords—ordered Rexhepi to home detention in the port of Guayaquil for “medical reasons.”

Then, unsurprisingly, he vanished. But his network rolled on—as did the violence. In 2023, an Ecuadorian presidential candidate denounced the sloppy handling of Rexhepi, resulting in his escape. The same candidate also pledged to take on his nation’s drug traffickers. He was assassinated less than two weeks before the election.

In November 2023, authorities caught up with Rexhepi, who was by then living in a villa in an Istanbul suburb under the name Benjamin Omar Perez Garcia.

Türkiye, where cocaine seizures spiked by 45 percent between 2020 and 2021—the most recent years on record—has been the focus of speculation as a potentially vital corridor for expanding the demand for cocaine into wealthy Middle Eastern markets.

As Mejdini said, “There’s no limit for them anymore. The model they have created to forge alliances, to cooperate with other foreigners, helps them go everywhere. Wherever there is demand, they are going to be the delivery guys.”

And that is precisely the key to collapsing Rexhepi’s booming empire and ending the illicit drug industry altogether: demand.

As long as people demand cocaine and other deadly drugs, Rexhepi and his fellow criminals are prepared to provide it—and will continue finding new and creative ways to overcome all obstacles.

But what if that demand dried up, through effective prevention initiatives like the Truth About Drugs?

With cooperation among enough law enforcement and lawmakers, with enough volunteers spreading the word at the grassroots level and, above all, with enough education to enough of our youth, the cultivation, trafficking and selling of lethal substances will no longer be a viable enterprise and will die an unlamented death.

You can’t sell a product nobody wants—and it’s a lesson we can’t teach Dritan Rexhepi and his cronies soon enough.